Background

UNITAR initiated the “Entrepreneurship and Leadership Youth Training Fellowship Programme” in South Sudan in 2015 to improve the capacities of young professionals in post-conflict countries. Implemented by the UNITAR Hiroshima Office, the programme aims to strengthen hard and soft skills of young professionals in the fields of entrepreneurship, project planning and implementation, and leadership. More specifically, the programme offers training in the design and implementation of organizational needs assessments (ONA), environmental analysis, stakeholder identification and integration, effective communication skills, post-conflict reconstruction processes, results chain, monitoring and evaluation tools, risks mitigation assessments, business model canvas, recognition of individual work styles, and teambuilding skills.

Implemented yearly since 2015, the programme takes place over six months and consists of two one-week domestic and two one-week international workshops. Besides the workshops, the participants undertake practical assignments adapted to their local and organizational needs, including an individual project, with the support of tutors and coaches. The coaches are former standout fellows who receive an additional training on “Coaching for Coaches”.

Since its inception, the Government and the People of Japan generously funded the UNITAR South Sudan Youth Entrepreneurship and Leadership Training Programme to drive social, environmental, and economic progress and contribute to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in South Sudan and across the region. UNITAR is genuinely grateful for the partnership to enhance the capacity of youth and drive the change for the good of the people and society as a whole.

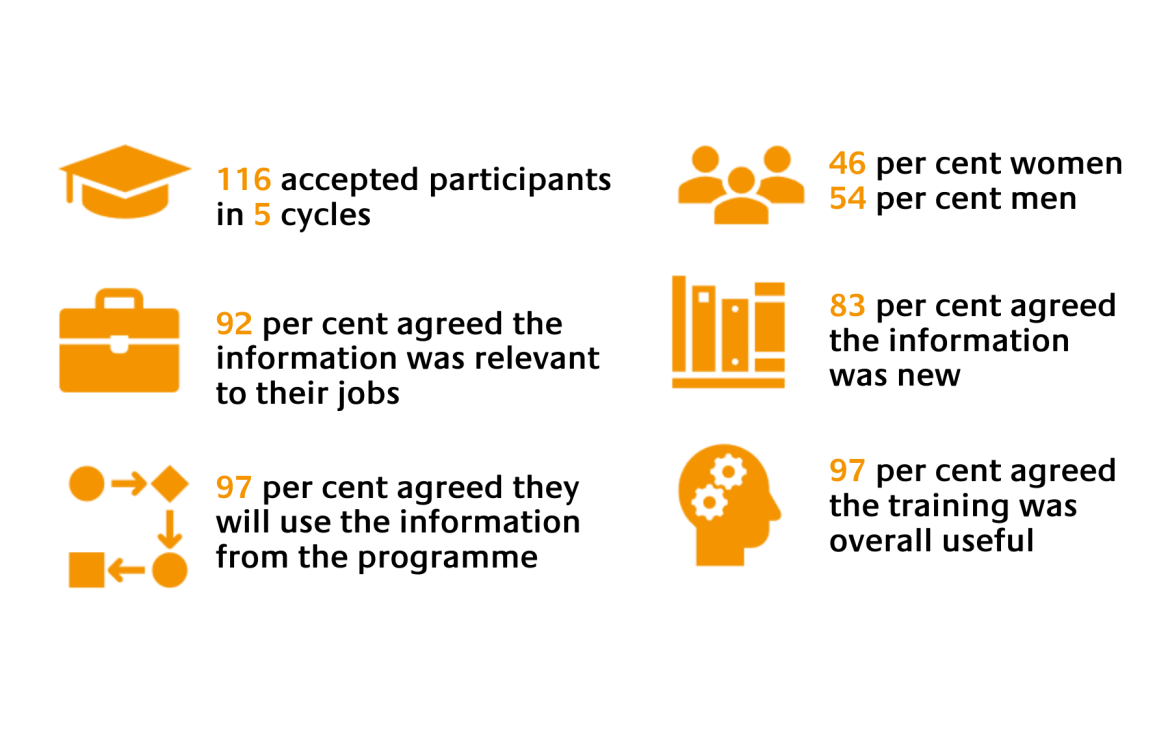

By the end of the fifth cycle, 116 participants (including 53 female participants, or 46 per cent) have taken part in the programme. On average, 83 per cent of the respondents from previous evaluation exercises agreed that the information provided during the fellowship programme was new to them, yet 92 per cent agreed it was relevant to their jobs, and 97 per cent indicated that they planned to use the new knowledge and skills.

To better understand the different ways participants have applied the knowledge and skills from the training, this Impact Story collects feedback from 44 participants from the 2015-2019 cycles and takes a close look at the post-training experiences of two fellows. The Impact Story is based on the results from a survey administered in March 2021 (with a 38 per cent response rate and two in-depth interviews.

Professional profile and application of knowledge and skills of survey respondents

At the moment of their participation in the programme, most of the survey respondents (75 per cent) were working in organizations focused on entrepreneurship, project management/implementation, or leadership. Of these, forty-eight per cent were junior or mid-level professionals and 25 per cent had managerial positions or were co-owners of SMEs or other projects. Also, many of the respondents (84 per cent) worked in governmental institutions, NGOs, or the private sector. Besides being professionally involved in the fellowship thematic programme areas, 61 per cent had already previous training in entrepreneurship, leadership skills, or project management/implementation.

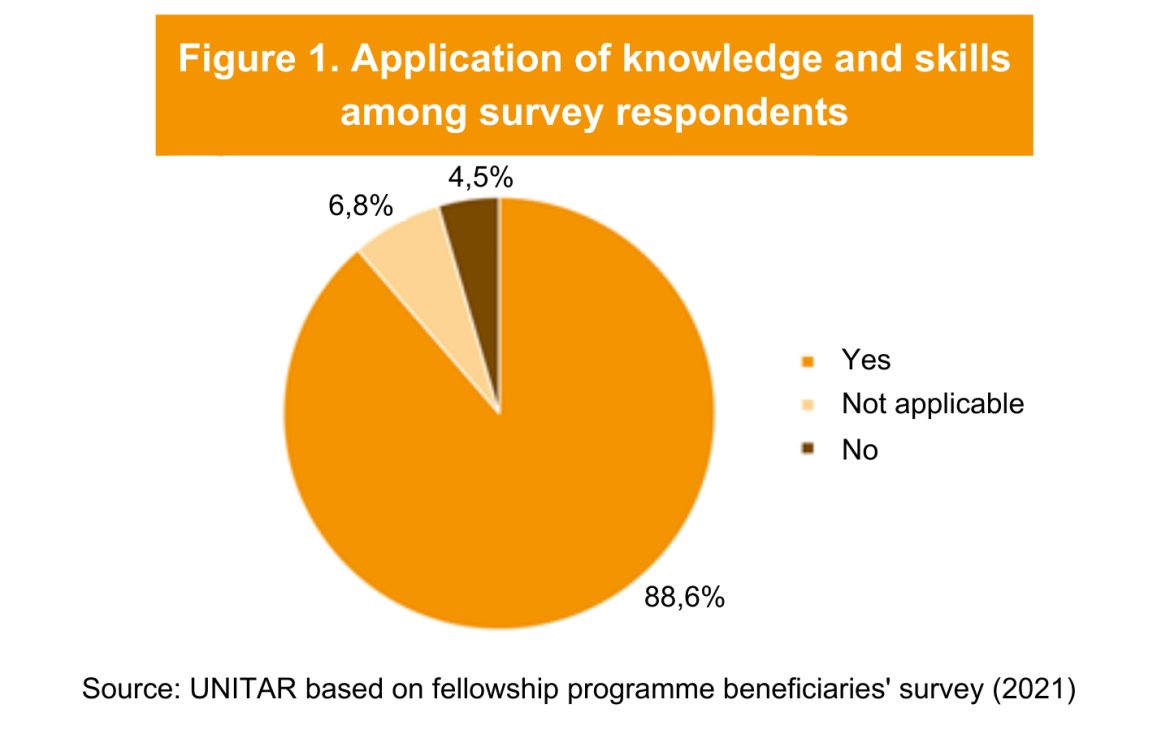

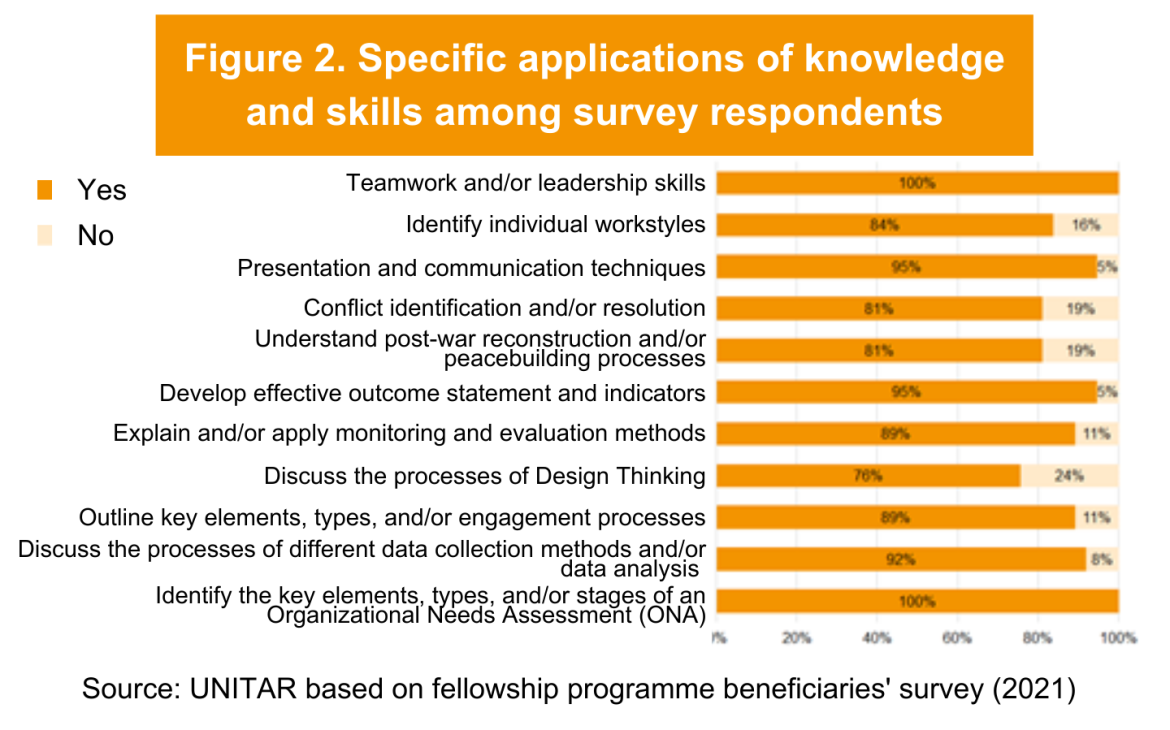

The engagement in areas directly linked to the topics of the programme is reflected in the high number of participants confirming application of knowledge and skills, with an application rate of 89 per cent. The programme participants have applied a combination of both soft and hard skills to their work (see figure 2). Specifically, survey respondents confirmed applying teamwork and leadership skills and application of ONA, specifically. Examples of application of these skills from the participants include: identifying needs during partner selection processes, emergency response needs assessment for flood in Internally Displaced People (IDP) camps and conflict-affected areas, incorporation of steps on how to conduct needs assessments in academic lectures, incorporation of teamwork and problem-solving strategies, leading capacity building on leadership and management skills at work, implementation of environmental needs assessments, among others.

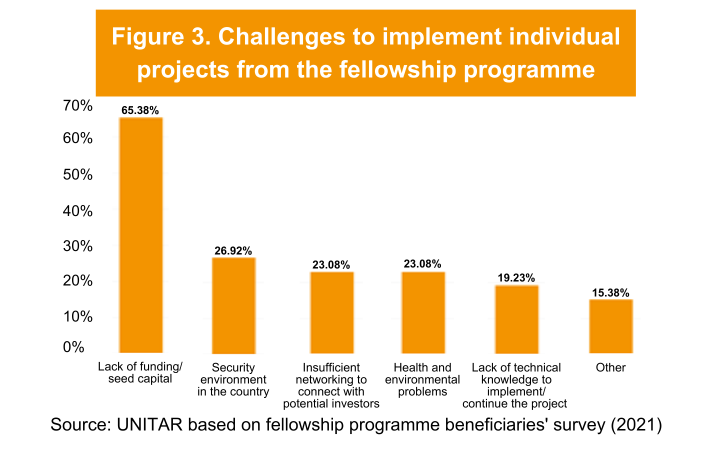

Some of the factors that enabled the application of knowledge and skills included confidence to apply the skills (84 per cent), good level of knowledge in the topics (79 per cent), training design and methodologies (74 per cent), and importance of the skills for job success (69 per cent). It is noted that a combination of personal endowments, characteristics of the workplace, and appropriate training design and methodologies are important for assuring the application of knowledge and skills. On the other hand, respondents identified lack of funds (66 per cent) as a preventing factor that of application of skills. This becomes clearer when digging into aspects that prevented the implementation of the participants’ individual projects. Although the proportion of respondents that have implemented their projects is high (37 per cent, equivalent to 15 participants), some others reported having had difficulties doing so. As shown in Figure 3, the four main reasons are lack of funding, the security environment in the country/lack of spaces to connect with potential investors and health and environmental problems (including COVID-19 complications).

Transferring skills and sharing ideas with others after the traineeship was also important for the programme. Most of the respondents stated they had shared ideas or knowledge from the course with their co-workers (97 per cent), members of their communities (86 per cent), former classmates or former fellows from the programme (82 per cent) and with mentors or coaches (65 per cent).

The coaching component boosted the knowledge and skills as well as the ways in which the skills were transferred. Former coaches responding to the survey expressed how coaching helped them enhance their skills, especially those related to leadership, communication and individual confidence (See Box 1); however, hard skills were also reinforced. Some former coaches also affirmed making themselves more available to transfer knowledge and skills to others after their coaching experience, even outside the programme.

Comments from former coaches

I learned that level of understanding differs from one person to another.

My experience as a coach for UNITAR has been fruitful because [I] got to interact and share ideas with fellows from different professions. As a coach [I] have learned that each individual is unique but we need to communicate and collaborate with each other to find solutions to the issues that we all face. Being a coach has made me more confident.

I began to realize that being a [c]oach is a continuous process of learning and very rewarding… [I] built confidence in me and renewed my memories, created a social and technical connection with the fellows in the program and the staff, [e]nhanced my knowledge base and skills acquisitions and therefore a paved way to expertise.

Impact Story - Christina Pita Luduku

Christina Pita Luduku

Lawyer – Co-founder of an independent law firm

Applying leadership skills to empower women professionals

Juba, South Sudan – 2015 Cycle. Christina is a hard-working woman and a leader in her professional field. She holds a degree in law with a diploma in human rights and is passionate about women’s rights. She decided to focus her research project on women’s rights in conflict, complex, and post-conflict situations. She has worked as an assistant legal counsel for the Ministry of Justice and Constitutional Affairs, as a consultant for UNITAR, and is currently the co-owner of a law firm that offers legal services primarily, but not exclusively, to NGOs. Christina also provides free legal counselling to NGOs and small initiatives, which she believes helps develop her community and improves her professional skills.

Before joining the programme, Christina worked for the Ministry of Justice and Constitutional Affairs and was either the only woman or, from time to time, one of very few women in the Ministry. At the time of the programme, she did not have previous experience in entrepreneurship or leadership, but she was interested in the topic since she believed that implementing good quality projects can bring about real changes, contrarily to what sometimes happened in the field of law, where changing the legal framework to create changes can take much more time.

Christina was very dedicated during the programme and was selected as a coach for the next editions. During her work as a coach from 2016 to 2019, Christina transferred the skills gained during the fellowship to new fellows in the programme. The coaching work was very demanding as she had to help with training facilitation during the day and support the fellow’s project proposals (e.g., reviewing, advising) during the evenings. Nonetheless, she considers the experience very worthwhile as this experience also improved her skills, especially her leadership skills. Christina says that the fellowship programme helped her develop her confidence by improving her communication and presentation skills, which she transferred to the fellows, especially to women.

Christina recalls one situation where one of the women she coached had an excellent project proposal, but experienced difficulties with presentation techniques. Christina was committed to helping her and coached her every day using her own progress and personal techniques as examples. In subsequent presentations, Christina could see the trainee’s progress in communicating her ideas. Christina also uses the learned leadership skills in her work as a lawyer. She is part of a women advocates association and has observed how sometimes women’s opinions are less valued or acknowledged than men’s. Then, she always reminds them and helped them express their ideas, incorporate leadership skills, and value their work.

Besides leadership skills, Christina has also applied hard skills in writing project proposals. She has assisted these processes in the women's advocate association by request of her colleagues in the group and in her work at the law firm. Some of her tasks in the law firm include drafting project proposals, constitutions for NGOs and contracts, where she can directly apply the knowledge from the programme. She also uses the monitoring tools and techniques to assist in the implementation of her client's projects. Christina recognizes this as an asset from the fellowship and notes that her colleagues do not have the same knowledge about monitoring tools.

The knowledge from the programme related to peacebuilding has also helped Christina in her day-to-day work. She sees the programme as having contributed to broadening perspectives on interpersonal relations, especially in post-conflict contexts like in South Sudan. She now can see that there is no point in getting angry with someone for a disagreement, but that it is better to leave things aside and "focus on what’s on the table" and be more careful in her relations with others to avoid damaging any bonds with her colleagues.

An additional factor from the programme that has contributed to the application of knowledge is networking. Christina is still in contact with other fellows, and they occasionally share time. This connection allows them to have updates on their individual projects and share work opportunities between them. For example, Christina's law firm assists NGOs in developing project proposals and when she sees that someone requires any specialized service she connects them with some of their fellow colleagues from the UNITAR programme.

Although Christina has been able to apply the skills from the course to her work as a lawyer (and providing training), she faced some challenges while trying to implement her individual project. Christina's project was linked to her work at the Ministry and consisted of providing legal aid services to women inmates in the Juba prison. Unfortunately, she had difficulties obtaining information from the prison administration and adequate support from her supervisor at work, as well as lack of funding to continue the project on her own.

Christina is very grateful for her participation in the UNITAR fellowship programme and hopes it can continue. She also would like to see many of the projects from her former fellows being implemented and hopes that there could be a mechanism to facilitate the initial seed funding of the projects.

Impact Story - Hakim Monykuer Awuok

Hakim Monykuer Awuok

Consultant – EmpowerKids South Sudan and Director for Cabinet Resolutions, Ministry of Cabinet Affairs

Conducting ONA to empower kids in South Sudan

Juba, South Sudan – 2016 Cycle. Hakim holds a bachelor’s degree in public administration and a master’s in public policy. Since 2014, he has worked as a consultant for EmpowerKids, an NGO working to improve educational opportunities for children in South Sudan, and, in parallel, for the Cabinet Resolutions Department of the Ministry of Cabinet Affairs since 2016. Having dedicated most of his work time to the NGO, Hakim decided to concentrate on the development and implementation of projects that could improve the opportunities of people in his country.

Before the programme, Hakim felt he needed to develop new knowledge that could enable his creativity and work performance when implementing projects. His biggest challenge was conducting needs assessments, and he decided to enroll in the programme. After the programme, Hakim feels very confident in conducting needs assessment and has noticed how applying this knowledge has improved the quality of his work. For Hakim, every community has multiple challenges. However, when you do not have the skills to differentiate the primary needs from all of the challenges, you will probably not succeed in implementing your projects because you only jump to a conclusion but cannot recognize the problems that require solutions first.

As a result of needs assessment exercises led by Hakim, new initiatives have been introduced to the work of the EmpowerKids. For example, Hakim’s team found that one of the causes of girl’s school absenteeism, and sometimes school dropout, was the lack of resources to purchase sanitary pads. When girls had their periods without appropriate menstrual care, they were sometimes bullied at school by fellow boys, which sometimes led to absenteeism. They realized that providing sanitary pads and awareness about the topic would be a solution to this problem. Then, Hakim’s team presented their results to the organization and searched for partners to implement an initiative in this regard. Now, they have introduced the Days for Girls (1) initiative in partnership with an organization in Uganda.

Similarly, as a result of another needs assessment they have improved the outreach of an existing project by promoting a free offline repository with the textbooks of South Sudanese schools oriented by the Ministry of Education. However, the results of the ONA indicated that many of the families do not have access to a digital device and could not access the textbooks. Consequently, they created a digital library in one of the secondary schools. They equipped a room with 50 solar-powered tablets where students can access the books freely (2). Hakim considered that without the fellowship the quality of his work would not be the same and he would probably have fewer opportunities to identify the real needs and implement these new initiatives.

Besides using needs assessments, Hakim also conducted two workshops for EmpowerKids to transfer knowledge to his colleagues. He also tried to apply some of the new knowledge to his work at the Ministry, but he did not receive adequate support from his supervisor.

Hakim considered that his educational background helped him to understand quickly and how better use the knowledge obtained during the programme. Networking was another factor that has helped him apply the skills. Given his experience working in the field, he can connect the ideas with potential partners easily through the organization in which he works. However, it is still a challenge to develop some initiatives on his own, such as his individual project from the fellowship. Hakim’s project was to train women refugees in handicrafts so that they could generate independent incomes. Nonetheless, it was difficult for him to obtain funding and he did not continue the project.

Hakim was invited to participate as a coach for the 2017 cycle. He says that it was a different experience in comparison to his participation as a fellow because from the beginning it was him acquiring the knowledge and giving it to somebody who wants to gain knowledge. A learning from the coaching experience was interacting with others. He learned how to approach a person to make him/her feel open to taking advice. The coaches received additional training before the start of the programme in Uganda. The workshop was concentrated on how to address the participants and explain the information to other adults and other communication techniques.

Hakim feels very proud of having been part of the fellowship programme, his experience as a coach and his achievements using adequate needs assessments. He hopes others can implement their projects, if UNITAR perhaps provides more support to connect with potential funders.

(1) https://empowerkidssouthsudan.com/initiative/days-for-girls/

(2) https://empowerkidssouthsudan.com/initiative/solar-spell/

Conclusion

The fellowship programme has been useful for improving participants’ work performance and has indeed generated changes in their professional lives. Both hard and soft skills have been applied by many of the participants. The design and implementation of ONA was suggested by many of the participants as one of the hard skills most largely applied. Soft skills were also commonly incorporated into their work, especially teamwork and leadership skills. The participants’ professional profile and previous training in fields related to the fellowship programme themes are likely factors helping to secure application of knowledge and skills. The training methodologies and support from coaches also represented opportunities to enhance the knowledge and skills.

Similar to other programmes previously evaluated, the implementation of individual projects was more difficult. Nonetheless, most of the participants are continuing to work on their projects and a considerable proportion have already implemented theirs. Some suggestions summarized from the participants in this regard are:

- Dedicate more time during the fellowship programme to improve the writing of grant proposals;

- Create a platform where fellows could market their projects or connect with potential investors or organizations interested in supporting the implementation of the projects; and

- Follow-up from mentors after the training.

The programme’s coaching component has helped those selected as coaches to enhance their hard skills and improve their soft skills, which they can sometimes implement in their workplaces. Besides, they can expand their networking opportunities when interacting with the programme fellows.

An unexpected result from the fellowship programme is the creation of a community by some of the fellows, where they do not only exchange their experiences and ideas, but it acts as a platform to generate job opportunities among them. Perhaps, better follow-up about this practice should be done and shared with new fellows as an opportunity to increase the likelihood of application of knowledge and skills from the course. UNITAR could consider formalizing and further supporting ongoing communities of practice.